The second Sunday in May can be complicated.

Tag Archives: daughterhood

Pantheon, One Fallen

I have been trying, and failing, to write about the Bill Cosby abuse allegations for weeks. I am finding it nearly impossible to talk about, because I am so sad.

On the surface of things, this story doesn’t touch me personally. I’ve never met Cosby. I don’t know any of the many women (23 at this writing) who have accused him of drugging and assaulting them. I believe these women, without ambiguity. And while I am distressed at how familiar this narrative is — the powerful man, the vulnerable girl or woman, the fear of not being believed, the threat or payoff to stay silent — that doesn’t account for how bereft I feel.

I am desolate over what has been revealed here, because Bill Cosby is one of my pantheon of fathers.

I’ve written before about my biological father, about his particular damage and how it made him behave in thoughtless, cruel ways. He and my mother split up when I was 6; I ceased all contact with him when I was in my early 30s. In-between, we waged a war of love and fury, estrangement and dark intimacy. He was, in many ways, a great love of mine. He was, in others, a malevolent force that nearly destroyed me. He was so many things to me, but a good father was not one of them.

For that, I had Pa Ingalls. James Evans. Atticus Finch. And Cliff Huxtable.

. . .

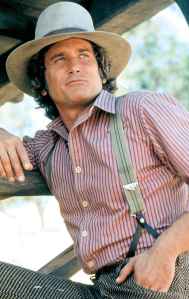

I was about to turn 5 when the 2-hour Little House on the Prairie movie premiered in 1974. Like many little girls, I was obsessed with Half-Pint and her braids, perfect Mary, the dinner pails and single room school, that bitch Nellie Oleson. (For the record, I met Alison Arngrim once, and she is delightful. What? Yeah that’s right, I interviewed Nellie Oleson when I worked at TV Land and it was even more amazing than you think it was.) But the real draw of this show, for me, was Pa. Charles Ingalls was a man you could look up to, a man who could shoot and ride and plant and reap, who could build his family a house and then fill it with music he played himself. This was a father, and I turned to him the way sunflowers turn their open faces towards the sun. I never read the books, because someone told me that Book Pa was actually sort of strict and a disciplinarian, and I wanted none of that. For me, Pa is bright blue eyes, moppish hair, social liberalism, a charming sense of humor, and a faithful, enduring, enlightened love for his wife and children.

. . .

Good Times also premiered in 1974, and I fell in love with the Evans family immediately. As an adult, I wrote about this show for TV Land, and I was shocked — I mean genuinely shocked — to realize they were poor and lived in a dangerous housing project. As a child, all I saw was they love they shared, the wholeness of their family. I wasn’t an idiot, I knew they weren’t wealthy, but anything they might have been lacking, might have been wanting for, was made insignificant by James Evans. Here was a deeply proud man who was willing to do what needed to be done, who worked two jobs at a time to provide for his family. And when that failed, he was cool enough to make money playing pool. He was a man who called his daughter Baby Girl in a way that felt protective and kind, that made the world safer. A man who was there for for his children, adored his wife, and navigated a brutal world with a steadfast power that awed me. This was a father. Poor? Hell, these people were rich as far as I could see.

. . .

There were years when I carried a copy of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird around with me wherever I went, tucked into my backpack. Atticus Finch made the world bearable. His humility, his passion for justice, his brilliance. The way he could shoot. The way he chose not to. His uncomplicated, profound love for his children. His compassion. His courage. His dignity, and the way he offered a sort of grace to everyone around him. Atticus was the definition of a good man, a gentleman, a man whose fundamental decency was the truest thing about him. This was a father, someone to look up to, who could guide you to the next right thing, the hard thing, every time. He would not fail you.

. . .

Which brings us to Cliff Huxtable.

I was 15 when The Cosby Show premiered in 1984. By then, my mother had remarried, and my biological father had come back into my life after disappearing for several years after the divorce. My stepfather is a good man, and he has treated me with kindness and love from the start. But it was complicated, being the daughter of these two fathers, both sort of strangers. It was messy, confusing. It was hard to know whom to trust, whom to love and how to love without feeling I was perpetrating some kind of betrayal against one of them.

For the Huxtables, life held no such complexities. There was no mistaking how comfortable these people were, no mistaking the joy and playfulness in that house, the saucy love between the parents, the comical throng of siblings. Cliff was present for his family — literally present, his office was downstairs — and he took such clear pleasure in his children, their achievements and quirks, their adorable babyhoods and teenage dramas. This was a father, one who would talk to you, listen to you, make you laugh. One who was genuinely engaged with who you were, and whom you might be someday. One who didn’t give you secrets to keep, unless it was that he’d given you chocolate cake for breakfast.

And he is lost to me now.

. . .

One of the largest parts of growing up is accepting the fact that your parents are people, with flaws and passions and hungers of their own, with their screwed up histories and regrets. Sometimes you realize they are dangerous, and the only thing for it is to build a wall between you. Maybe you forgive. Maybe you can’t. But at some point, if you are to have anything for yourself, you find a way to stop blaming them. You take responsibility. You take up the threads of your life and weave a tapestry of your own design.

I know this.

But it is hitting me hard, this realization about Bill Cosby. It is a fresh hurt in a place I’ve been wounded before. Because I believed Cliff Huxtable was like Pa and James and Atticus. I believed he was the kind of father who could keep me safe from men like Bill Cosby, men like my own father. And as much as I want to separate the character from the man, they are inextricable. When we talk about Bill Cosby we are talking about someone who, by reputable accounts that I believe, would drug and abuse more than 20 women while publicly joking about hoagies. Cliff feels like a lie now, the kind of lie my father would tell his friends and colleagues about our relationship, the kind of lie I was meant to agree with, about how close we were and how proud he was of me, while all the while he was hurting me in ways no one could see. This is personal. It is a tangible loss in the father-shaped place I have been trying to fill since I was 6.

Make no mistake. I stand with the women who accuse him. But I stand with a broken heart.

It’s Called FaceTime for a Reason

This summer, my then 8-year-old daughter, Emerson, experienced two important rites of passage.

First, she became the object of a young man’s affection. This boy, whom we’ll call DG, had it bad for my moppet. So bad, in fact, that he asked if she had email, and told her that if she did NOT have email he’d make an email for her, so they could write during the evenings and over the weekend, when he was bereft of her company.

She told me this matter-of-factly one hot July night after camp, as she shoveled mac-n-cheese into her summer pink face. My baby, who has my pointy chin and round cheeks, her Daddy’s beautiful mouth, and more hair than anyone has a right to. My sweet little girl, who loves dragons and making things out of clay. My precious child, who is the kindest, funniest, and most generous person I have ever known.

“Well, Mama. Do I?” she asked.

“Do you what?”

“Do I have email?”

“Yes, my darling, you do. You have email so you can write to Grandma and Grandpa in Florida, and Grandma in Connecticut, and Yaya.” (That’s her nickname for my best friend, Lisa.)

“Well write it down for me, so I can give it to DG and he can send me an email.”

I didn’t just hand over her email address, of course. First I confirmed that this person was actually another child and not a 40-year-old ice cream vendor who hands out balloons to his “special” customers, but you have to climb into the back of the truck — which is really just a white van that he painted to look like an ice cream truck — to get your balloon (I watched far too many After School Specials growing up). Cue the epic eye rolling as she assured me that YES MAMA he’s a KID! He’s 10! We then had a giggly conversation where she admitted DG had a crush on her, and while she didn’t have a crush on HIM, she liked the fact that he had a crush on HER quite a lot.

I told her that she’s under no obligation to like him just because he likes her, that she doesn’t have to give anyone her email or phone number or smile for them or tell them her name or respond AT ALL just because a boy likes her. But if she IS going to be friends with him, she should understand that he has more-than-friend feelings for her, and be kind to him. And that if he, or anyone else for that matter, ever makes her feel uncomfortable or hurts her feelings or pressures her to be more than friends when she just wants to be friends then she should immediately tell me or her Daddy, and we will kill him. With our bare hands. And make it hurt. Bad.

Maybe I didn’t say that last part.

At the time Emerson didn’t have her own device on which to receive email. No iPad or iPhone or computer to call her own, because she is the most deprived child in all the land of Brooklyn. Her email came through on my iPhone, however, and so I was privy to the besotted musings of this 10-year-old Romeo. Here’s how it worked: He would send a message. I would see it on my phone, but not open it. I’d go home after work and tell her she had email. She’d take my phone and read the message, giggle, and then hand the phone back to me so I could type her dictated response, because I am her secretary. Sometimes she’d get bored and wander away, and I’d go scrambling after her because it is one thing to be transcribing a message from an 8-year-old girl to a 10-year-old boy, and quite another to be texting said 10-year-old boy by myself.

Things got serious when he started in with the emojis.

This went on for quite a few weeks. He even emailed her while we were away on vacation, counting down the days until she returned to camp, pumping out a string of emojis we had to consult a glossary to decipher. And then, sure as winter follows fall, came rite of passage number two: He dumped her. She went to camp one day, and he casually informed her that they were breaking up, but could still stay friends. She shrugged it off — she really hadn’t liked him that way, and was content with his ongoing friendship — but I admit to feeling a little miffed. I’d gotten pretty invested in all those emojis after all.

In August, for her 9th birthday, we got Emerson an iPad. She was so happy she cried. Mostly this iPad has been used for watching Wild Kratts (#TeamChris forever), taking photos of herself using Photo Booth, emailing grandparents, and FaceTiming Yaya.

And about a week ago, she used it to FaceTime DG.

I do not know what her motivation was. I think she was just missing her friend. He gleefully shouted her name when he realized it was her, and they talked for a long time, about school and games they were playing online, about his parents’ divorce and his brother and sister, about her fish. I didn’t eavesdrop – she did it in front of me, sitting on the couch. It was sweet, and tender. He told her he cared about her, and missed her, and was so happy to see her face.

He is a lover, this DG. His vulnerability slays me.

This is just the beginning, of course. The beginning of the boys and men (and perhaps women, who knows?) who will love her, whom she will love. And I want it all for her, all the ecstatic wonders and heart-cracking pain that is loving another person. The lavender-scented joy and the eating a tub of frosting in the bathtub while crying. I wish her everything, all of it, every electric moment of love and passion, eventually, when the time comes.

But first, this girl and I had some business to take care of.

I found her curled up on her bed, reading one of the BONE books. “Hey Emmy,” I said. “Can we have a conversation?” She put her book to one side and turned her open, sweet face to me.

“Sure. Am I in trouble?”

“Of course not. Why would you think you’re in trouble?”

“Well, what do you want to have a conversation about?”

“I want to have a conversation about FaceTime.”

I nude modeled in college, for sketch classes, and painting classes. I loved it. During breaks I would slip into a white robe, light a cigarette, and wander through the rows of easels, looking at the canvases and seeing myself the way others saw me. It completely changed the way I thought and felt about my body, made me appreciate the curved landscape of my belly and hips, my neck and breasts, the wild tumble of my unruly hair. I had a lover who photographed me nude, and I trusted him with my life. When we broke up, he gave me the photos, and the negatives.

I didn’t tell my daughter any of that. I will, someday, when my 20-year-old innocence and wildness can serve as a fond anecdote, rather than a model for her own behavior. Instead, I told her that sometimes when people have phones or other devices with cameras they can get a little silly and take pictures of their bodies, like their tushies, and then send them to other people. She laughed at that, thought it was ridiculous. And it is, I told her, it is very silly, but it is also sort of serious, because the Internet is an endless place, where nothing ever truly goes away. And even if you just send a photo like that as a joke, to someone you trust, once it leaves your Photos it might go anywhere. So we struck a deal. She will never take a photo, or video, or FaceTime of any part of herself below the neck. In a nervous spurt of creativity, I even made up a cheerful rhyme, to help her remember:

If it is not of your face, do not send it anyplace.

I also told her that if anyone sends her a photo of anything but their face she’s to show me or her Daddy immediately, and we’ll help her take the right next steps. If they show her any non-face parts on FaceTime, she’s to shut it down and come tell us.

I’m almost completely certain this was the right thing to do. She’s young, she’s so exquisitely young, but if you’re old enough to have your own iPad, know how to shoot photos and use FaceTime, and have a romantic boy to FaceTime with, then I think you’re old enough for this conversation. I think this conversation is required.

The world is so wide and full, so delicious and riotous. And I want her to have all of it. But for now, only from the neck up.

Grown ups

My husband, Jonathan, and I both had the kind of childhoods where we were left to look out for ourselves a lot. Not because we weren’t loved. We were, very much, and also well provided for. But in the houses where we were raised, there were larger issues that needed attention, and those concerns took priority.

When I was a little girl, my mother was consumed with keeping us safe from my father’s selfish cruelty and the repercussions of his philandering. And then later, after she kicked him out, she devoted herself to repairing the damage he’d left behind. She built a career, patched herself back together, paid off the debt he’d accumulated, met my stepfather, fell in love, bought a house, became a success. She was busy, yo. She had business to take care of.

In Jonathan’s house, his sister was fighting a battle with her own personal demons, which I won’t detail here because they are her business and she has been well for a long time. I bring it up only because her difficulties were paramount for many years, the most important thing in his family.

As a result, Jonathan and I both have a sort of patchwork understanding of what it means to be taken care of, to rely on another person to help solve problems. Neither one of us is very good at asking for help, preferring to gut things out on our own. And we share a specific kind of panic when things go awry, a knee-jerk, wide-eyed, deer in the headlights reaction that’s best summed up as, “Oh shit. Now what?” We’ll joke that we need an adult to come help us figure out what to make for dinner, deal with paperwork, make plans. We’re only sort of kidding.

On Christmas morning our heat broke. I’m not good with mechanical technology, so I’m not sure how best to explain what happened except to tell you it was extremely cold and when I moved the thingy on the thermostat there was no heat. Jonathan and I had one of those conversations where you keep a crazy-eyed smile on your face and pretend everything is fine because your kid is there, opening presents while wearing a parka and a hat, but really you are freaking the hell out because the heat is broken and it’s Christmas day and you need a grown up and that’s supposed to be you but you don’t know what the hell to do because all of a sudden you are 16 again and home alone with a situation that is way out of your league and probably this is going to cost all the money and then you will have to sell your apartment and live in a box. (Living in a box is my worst-case scenario and I tend to go there immediately when the slightest thing goes wrong.)

Eventually we remembered we have a management company for just this sort of occasion, so we emailed them. And then we remembered we have a building supervisor, so we called him. They both got back to us quickly, the management company offering the names and numbers of emergency plumbers. (Oh dear God, I thought, do you know how much a plumber will charge on Christmas???? We’ll be living in a box by New Year’s. LIVING IN A BOX.) Meanwhile, the Super generously volunteered to come over and see if there was anything he could do to help. But we were due to leave for Jonathan’s parents’ house in Connecticut in a few hours, and so we told the Super we’d call him when we returned on Friday.

We had a lovely, if slightly fretful (NO HEAT LIVING IN A BOX OUR CHILD WILL HAVE BLUE LIPS WHILE SHE SIPS ICY SKIM MILK FROM A TIN CUP WEARING FINGERLESS GLOVES OH GOD MY LIFE IS A DICKENS’ NOVEL), visit with Jonathan’s family, and then we returned to our freezing cold apartment on Friday night. We called the Super, who told us he’d “bled the whole floor” in our absence (I assume this is a heating related thing and not a reference to The Shining) and we should try turning on the heat and see if something happened. Nothing happened. We could hear water gurgling in the pipes but the baseboards stayed cold. We called back the Super and told him what was going on, and he gave us the number for a heating repair company and told us to call them, because it sounded like it might be a pilot light problem.

And that’s when it happened. That’s when I realized there ARE grown ups in our house, and everything was going to be fine.

Because when we bought the apartment I signed up for a service plan with the heating repair company the Super had just told us to call, and I knew where I’d filed the paperwork, and I’d paid the renewal on time, and when I called them they told me that because I’d purchased the cadillac plan, they’d be here first thing in the morning, and the repairs would be covered (by which I mean free, by which I mean there’s no need to pay them any money for this emergency repair service, so no living in a box, for now at least, and, pardon my digression, but this is why you should get the good insurance, everyone who asked my advice about which health plan to choose when we were doing open enrollment at work).

We had a chilly night, but it hardly mattered. I gave Emerson a steamy hot bath, dressed her in two pairs of pajamas and wrapped her in a fleece blanket, slept with my icy feet pressed against Jon’s warm legs all night (he’s part potbellied stove, I swear). This morning the repairman came and it was the pilot light, easily fixed. We gave him an exorbitant tip, what Jonathan calls the “relief tax.” The heat is now blasting and we’re all watching Batman: The Brave and The Bold on Netflix.

I know it doesn’t sound like much, particularly if you grew up in the kind of house where, if the heat went out, someone lit a fire and gave you a mug of hot chocolate to wrap your cold hands around while they made things right again. Where your worries were appropriately sized. But for us, kids who had to figure out grown up things, who had to bandage our own wounds and soothe our own hurts, fix what was broken on our own as best we could and instinctively knew not to ask for much from the exhausted, preoccupied people around us, it is deeply comforting to know that there are finally grown ups at home. Two of them, even. And while we may be watching cartoons and eating cake for breakfast, all is well here. All is safe, and whole, and warm.

Black Box

My mother annoys me.

I love her, and we get along fine. Better than fine, frequently. We make each other laugh, and we’re on the same side more often than not. She adores my daughter and treats her like royalty, like Emerson is here to do something very important and my mother’s job is to nurture her until she fulfills her destiny. And that fills me with tenderness.

Even so. my mother annoys me. Which is an improvement, because she used to drive me to the acidic, smoking, volcanic glass edges of shrieking rage. But after 10+ years of therapy that in large part involved dissecting, pinning open, labeling, cataloging, and filing away everything dark between us — from the queasy vibrating terrors of paradigm altering betrayal to petty hurt feelings — I can say with utter honesty that I love her dearly, and she annoys me.

I’ve also come to realize that, when it truly mattered, she gave me what I needed most.

I’ve been thinking about this because my favorite professor from college has asked me to write a little essay about the value of a theatre education, for a display in the arts building on campus. And the surprise is — it really was valuable. (Why is this surprising? Because while other people were studying for calculus exams, I was lying on the floor in creative rest position pretending to smell an orange.)

I didn’t end up making a life in the theatre, but my education gave me the ability to stand in an empty black room and create worlds. It taught me the rhythm and sensuality of language, the craft of story. It taught me how to swallow my fear, stand up in front of strangers, and persuade them to follow me into laughter or terror or grief. It gave me a bright, clear voice, and the ability to drop or recall my New York accent at will. It taught me that evil can be charming, that goodness can be complicated, that love is sometimes a dagger plunged into your beloved’s heart. It taught me how to think on my feet, how to be in the moment. It taught me how to concept, how to improvise, how to riff an idea with a partner like we’re playing jazz. It gave me a lexicon of private jokes, which make musical parodies and movies about show business infinitely funnier to me than they are to civilians (that’s what theatre people call non-theatre people, and I’m still delighted to be counted in the club, however marginally). It gave me a home, where passion and a black turtleneck were the only price of entry, and everyone valued my broken places and moody sadness. It gave me a safe place to be, until I could make the world safe for myself.

And the reason I was able to pass into this state of grace? To spend my days reading Greek myth and Shakespeare, my nights playing onstage with friends I loved so much they still feel like long-lost family. To wrestle with ancient passions, and pain, and elemental comedy. To be part of something so much larger, so much brighter, so much more complete, so much BETTER than I could imagine real life could be. Something I needed, craved, more than food, more than air, more than love.

Because my mother let me major in theatre.

When I was in college, I knew so many people who were majoring in English, in Communications, not because this was what they wanted or cared about, but because their parents wouldn’t allow them to major in theatre. Because their parents threatened to pull their tuition if they did. As an adult, I have met 50-year-olds who still wistfully look back on those days and wish they could have been braver, could have declared that theatre major, declared themselves.

But not me. I have my regrets, but they are all of my own making. Because my mother not only allowed me to declare a theatre major, she encouraged it. Encouraged me to run with it, as far as I could. To lie on that floor and SMELL THAT ORANGE like no one had ever smelled an orange before. And more. She took me to see Malkovich in “Burn This,” to countless musicals, to the opera, to the ballet. She paid for Saturday theatre school in Manhattan, for performing arts camp. She came to every show, even if she had to drive 4 hours to see me play farmer’s daughter #6 in “Oklahoma.” She joyfully made space in our living room for the “Godspell” set, for the elephant we made for “Barnum.” She welcomed home an endless cast of romantic boys and dramatic girls, all invited to stay as long as they needed to and eat all the American Cheese in the refrigerator, provided they called their mothers first and got permission.

My mother annoys me. In a flash, she can slip a thin silver knife under my skin and make me bleed, just with an offhand remark. And I know I hurt her too. That she craves more closeness with me, and I can be selfish and withholding with my affection. That I struggle to forgive what she believes should be forgotten.

But when it mattered. When it truly mattered, she gave me everything I needed. And then some.

And that is where I’m bringing the curtain down on this one.